Southwest Utrecht Regional Adaptation

To render the Utrecht Southwest region climate-proof and water-resilient, collaboration within the region is vitally important. For that reason, on 1 January 2020, the Utrecht Southwest Working Region set up the Water and Climate Network, in concert with seventeen partners. That same year, the Network set up a Regional Adaptation Strategy (RAS), setting out the vision and ambitions for collaborating on climate adaptation. On 28 January, the RAS was eagerly endorsed by all the partners.

How has the strategy been developed?

A working group has drawn up the RAS, in coordination with the network partners and several external partners such as the national government, businesses, NGOs, and local residents. The strategy is based on insights from the regional stress test and a KNMI report on the region’s current and expected climate. The two documents date from 2018 and provide insight into the region’s vulnerabilities in terms of waterlogging, heat, drought, and flooding. Furthermore, in the build-up to the RAS, the Water and Climate Network has conducted several risk dialogues with the seventeen partners and other parties: what risks are we going to accept and what risks do we need to address?

How vulnerable is the region to waterlogging?

According to the RAS, annual precipitation volumes have risen by 30 per cent over the past century, whilst the number of torrential rain days has doubled from 3 to 6 days a year. Waterlogging can occur at the foot of the Utrechtse Heuvelrug range, in the peat grassland area where water cannot be pumped away, and in built up areas where problems can mainly be attributed to the high proportion of pavement.

One of the targets set out in the RAS is that an hourly rainfall of 70 mm must not result in waterlogging: this is a lower limit. Some of the other goals for 2050 are:

- Creating an extensive green-blue network in urban areas, which during extreme downpours will ensure optimum water retention and storage in the soil and water system;

- Rendering vital and vulnerable functions water-resilient;

- Raising awareness among local residents and businesses in order to encourage them to retain water on their own premises wherever possible.

How vulnerable is the region to heat?

Over the past century, average temperatures in this region have risen by approximately 2 °C; the number of summery days has also increased. This could lead to the failure of such vital and vulnerable functions as electricity and bridges, whilst adding to the probability of nature fires. Furthermore, heat entails a higher probability of damage to crops. In urban areas, heat will cause particularly more heat stress and health issues, as the perceived temperature will rise faster here compared to rural areas. In addition, heat is conducive to the growth of blue-green algae, which will compromise the quality of swimming water.

Some of the goals for 2050 in terms of combating heat issues:

- Reducing the difference in perceived temperature (PET) between built and rural areas to a maximum of 5 degrees;

- Preserving the quality of surface water at a level that warrants its use during prolonged periods of extreme heat or drought;

- Local residents and business must have heat-proofed their premises to the maximum possible extent.

How vulnerable is the region to drought?

Over the past few years, the region has already experienced many drought-related issues. The sandy soils of the Utrechtse Heuvelrug range are particularly prone to drought, which increases the probability of damage to crops, nature, and biodiversity, and adds to the probability of nature fires. The peat grassland area is prone to rapid soil subsidence during dry periods, whilst in built up areas, houses and infrastructure can sustain damage because of foundations falling dry and the soil settling. Drought increases the risk of water shortages for urban greenery, agriculture, and fruit orchards. In addition, drought compromises the quality of water that is used for the irrigation of greenery and crops. Furthermore, drought can face the shipping sector with sub-standard water levels.

A random selection of the drought-related goals for 2050 set out in the RAS:

- Maximum local water retention through water infiltration in the soil;

- Preventing prolonged drought from causing dehydration of or damage to rural areas and built up environments;

- Gearing spatial planning to the natural groundwater levels and the availability of fresh water during periods of drought.

How vulnerable is the region to flooding?

As a result of climate change, the rivers need to discharge larger volumes of water and cope with increasing peak volumes. Furthermore, in the future, the rising sea level may cause increasingly higher river water levels, which adds to the risk of flooding in the region. The Water and Climate Network has adopted a three-tier approach to flood risk management:

- Prevention: preventing flooding to the maximum possible extent, by way of dykes and dams;

- Reducing the impact of flooding through spatial planning;

- Preparing areas at the organisational level for the impact of flooding, e.g., creating options for evacuation and shelters.

The RAS sets out that by 2050, the region will have reduced the impact of flooding, optimised evacuation options, and enhanced its resilience in the purview of recovery. Furthermore, by 2050, contingency plans will be up to par, whilst disaster management staff will be properly educated, trained, and drilled.

On the basis of risk dialogues, the RAS goals will be elaborated into concrete goals on the implementation agenda. In addition, an integrated approach to the four issues of waterlogging, heat, drought, and flood protection is important. To this end, the Water and Climate Network is following seven strategic tracks:

- Climate-adaptive new construction and restructuring: designing houses with due consideration for the issues of waterlogging, heat, drought, and flood protection. Wherever possible, fostering other taskings, such as the energy transition and biodiversity;

- The city as a sponge: local rainwater retention and storage, to enable its utilisation during dry periods;

- Liveability in times of heat: ensuring sufficient green spaces in the city to provide cooling and shade; enhancing the green-blue grids within the built environment. Having such grids tie in with regional green structures wherever possible;

- Climate-adaptive agriculture and nature development: existing nature benefits most from water retention, whilst new nature must mainly be resilient against drought and nature fires. For that reason, wet nature must be retained and connected to other green-blue structures extending into the urban areas. Agriculture will need to adapt to climate change by opting for certain crops and systems;

- Climate impact reduction for vital and vulnerable functions: failure of such key functions as IT or the power supply, as a result of, e.g., flooding can jeopardise national security. That is why it is imperative for such functions to withstand the impact of climate change, now and in the future;

- Enhancing the natural (water) system: on account of more and increasingly severe torrential rain, in combination with increased periods of extreme drought, rainwater collection and retention is becoming increasingly important. For that reason, the water system must be reinforced, whilst the soil system must be enhanced to increase the soil’s capacity for water absorption and water retention;

- Climate awareness and action perspectives for local residents and businesses: involving local residents, businesses, and other private parties in the climate adaptation tasking and raising their climate awareness. Focusing on the positive message: a green environment enhances liveability and the beauty of our region.

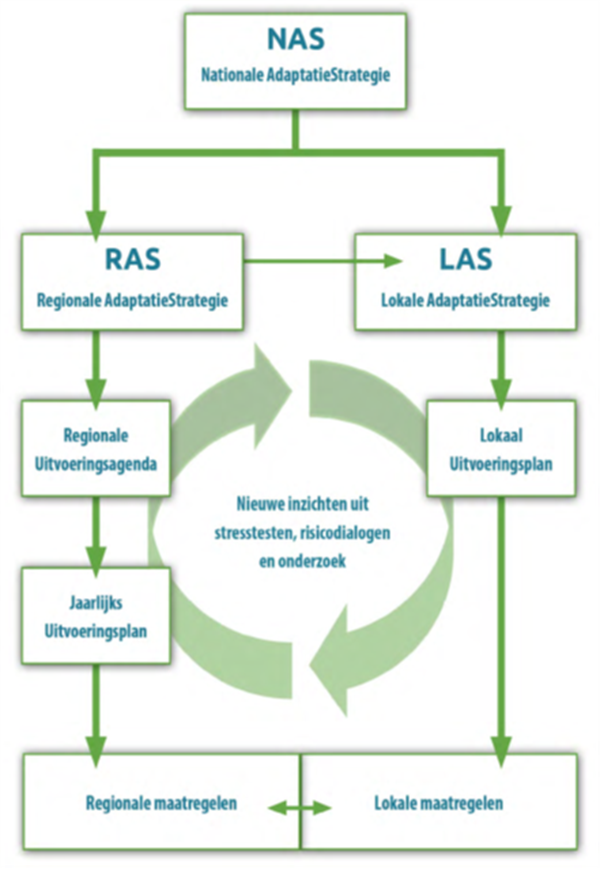

How does the RAS link up with local strategies?

The RAS and the regional implementation programme in which the goals are elaborated in more concrete terms interlink regional climate and water taskings. They thus provide a basis for local municipal policy and for local adaptation strategies. Fourteen municipalities are involved in the RAS: they are gearing their local policies and strategies to the RAS yet remain responsible for their own climate policies. Furthermore, implementation calls for a tailored approach. The RAS thus constitutes a first step rather than a blueprint for local adaptation strategies. Within the Water and Climate Network, the municipalities, the province, the Security Region, and the district water board are encouraging and learning from one another.

Special features

During the Climate Summit of 28 January 2021, the Water and Climate Network festively embraced the RAS under the motto of HoeRAS! We are setting to work! In addition, the working group has already embarked on an implementation programme which sets out agreements on who will be doing what, on the scheduling, and on funding. The programme will be based on the RAS and on the risk dialogues that the Network will continue to conduct.

Lessons to be learned

The working group has spent a relatively long time contemplating the substantiation of the RAS. Ultimately, they just started to write, whereupon the RAS gradually crystallised. In hindsight, the working group might have done better to start writing sooner.

Contact person

Koen te Velde

Netwerk Water en Klimaat

Koen.te.velde@hdsr.nl